The Big Picture

Recovery Spirituality

By Ernest Kurtz (Adjunct Assistant Research Scientist, Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan Medical School) and William L. White (Emeritus Senior Research Consultant, Chestnut Health Systems). Originally published on January 27, 2015

Introduction

Slaying The DragonAlthough addiction recovery mutual aid dates from the mid-eighteenth century, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) is the benchmark by which past and present mutual-aid groups are measured . AA has earned that distinction by its membership size and international dispersion, its organizational longevity, its influence on professionally directed addiction treatment, the breadth and depth of AA-related historical and scientific research, and AA’s wide adaptation to other problems of living .

The early history of Alcoholics Anonymous is well-documented within AA’s own literature , through independent historical scholarship , and through the recent proliferation of biographies of key figures in AAʼs story. Jeff Sandozʼs article in this issue summarizes the well-known “spiritual rather than religious” framework of alcoholism recovery detailed in AA’s two basic texts . Intriguingly, this “simple program” had by even two decades ago generated thousands of interpretive books, articles, and commentaries, usually revealing more about the authors than about AA .

One large reason lies behind this plethora of publications by AA attackers, defenders, and interested bystanders all struggling to define what Alcoholics Anonymous is and is not: the reality that AA is so decentralized that in a very real sense, there really is no such single entity as “Alcoholics Anonymous” – only AA members and local AA groups that reflect a broad and ever increasing variety of AA experience. To suggest that Alcoholics Anonymous represents a “one size fits all approach” to alcoholism recovery, as some critics are prone to do, ignores the actual rich diversity of AA experience in local AA groups and the diverse cultural, religious, and political contexts in which AA is flourishing internationally .

That difficulty is compounded because most who comment on Alcoholics Anonymous attend too much to its Twelve Steps, ignoring its organizationally more significant Twelve Traditions. AA’s Twelve Traditions underlie and make not only possible but inevitable the vast varieties among AA groups. Anyone wishing to comment seriously on Alcoholics Anonymous must think carefully about how the reality of that deeply internalized organizational blueprint may influence what they observe. The sociologist Robin Room, who has done so, has suggested that its Traditions may be AA’s greatest contribution to society, offering as they do a tested pattern for living a chastened individualism .

Newcomers to Alcoholics Anonymous are advised, “Try to attend ninety meetings in ninety days”. On a superficial but valid level, this encourages immersion in the AA program. But more significantly, this gentle mandate pushes the newcomer to try out many different meetings, hopefully to find some that fit his style, meetings at which she discovers a real sense of being “at home”.

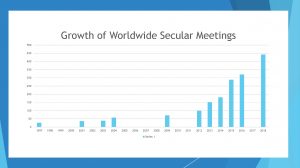

There are two broad patterns of diversification within the history of AA. The first occurs through organizational schism, when one or more members experience incongruity between their personal beliefs and AA practices, prompting them to abandon Alcoholics Anonymous and start an organization that offers an alternative to the AA approach. This process is reflected in the genealogy of AA adaptations and alternatives. These span religious alternatives (e.g., Alcoholics Victorious, 1948; Alcoholics for Christ, 1977: Millati Islami, 1989; Celebrate Recovery, 1991; Buddhist Recovery Network, 2008); (2) alternatives for other drug dependencies (e.g., Addicts Anonymous, 1947; Narcotics Anonymous, 1950/1953; Synanon, 1958; Cocaine Anonymous, 1982); (3) gender-specific alternatives (Women for Sobriety, 1975) ; (4) secular alternatives (e.g., Secular Organizations for Sobriety , 1985; Rational Recovery, 1986 ; SMART Recovery, 1994); and (5) moderation-based mutual support (Moderation Management, 1994) .

The second pattern of diversification occurs when individuals or subgroups seek and promote different styles of recovery within AA itself. This latter trend includes organizational adjuncts for AA members who pursue spiritual growth through a particular religious orientation – “11th Step Groups” (e.g., Calix Society, 1947; Jewish Alcoholics, Chemically Dependent People and Significant Others [J.A.C.S.], 1979) – and adaptations that seek either to secularize or to Christianize AA history and practice. The former include explicitly secular groups within AA (Alcoholics Anonymous for Atheists and Agnostics, 1975, and other groups); the latter involve groups that promote a more spiritual/religious focus within meetings (the “Primary Purpose” and “Back to Basics” movements).

These divergent wings of belief within AA and the proliferation of spiritual, religious, and secular alternatives to AA are unfolding within a larger recognition of the legitimacy of multiple pathways and styles of long-term addiction recovery.

The authors have been involved in sustained investigations into the “varieties of recovery experience” and have published articles on a wide spectrum of addiction recovery mutual aid organizations. We have conducted historical investigations of spiritual, religious, and secular recovery mutual aid groups, published interviews with key recovery mutual aid leaders, and helped develop a key Mutual Aid Guide. Through perspectives drawn from these experiences, we will focus in this article on the growing varieties of AA experience, with particular emphasis on the emergence of an atheist/agnostic wing within AA and what this development potentially means for the future of secularization or religious revivalism within Alcoholics Anonymous.

3. The Historical Context

Bill W.Alcoholics Anonymous began in the 1930s within the Oxford Group, an attempt to recapture “First Century Christianity”. Although AA early departed those roots, first in New York City, by 1940 also in its Akron, Ohio, birthplace, a strong religious tinge perdured, most evident in its “Big Book” chapter “We Agnostics”, which blandly assumed that all who approached the fellowship would find God. But there were early dissenters; one – atheist Jimmy B. – had a profound effect summarized in the addition of the phrase “as we understand Him” after the word “God” in the 3rd and 11th of AA’s 12 Steps.

There were others. Robert Thomsenʼs 1975 biography, Bill W., based primarily on extensive interviews with Wilson, offered a description of the late 1930s Tuesday evening meetings at the Wilson’s Clinton Street Brooklyn home:

There were agnostics in the Tuesday night group, and several hardcore atheists who objected to any mention of God. On many evenings Bill had to remember his first meeting with Ebby. He’d been told to ask for help from anything he believed in. These men, he could see, believed in each other and in the strength of the group. At some time each of them had been totally unable to stop drinking on his own, yet when two of them had worked at it together, somehow they had become more powerful and they had finally been able to stop. This, then – whatever it was that occurred between them – was what they could accept as a power greater than themselves”.

But such individuals were exceptional during AAʼs early years and even beyond. During World War II and the decade of the 1950s, sociologists noted the religiosity of an American public conscious of being confronted by “godless atheistic communism”. The period is aptly summed up in social philosopher Will Herbergʼs best-selling description of American reality in Protestant, Catholic, Jew, by President-elect Dwight David Eisenhower’s often mocked declaration, “Our government makes no sense unless it is founded on a deeply-felt religious faith – and I don’t care what it is”, and by Stephen J. Whitfieldʼs post-Cold War summary of the era. The counter-cultural 1960s, not least because of the assassinations and war that blotted that decade, witnessed a fraying of that faith.

Over that decade and the next, especially in the mid-1970s, those who complained of the religiosity” of Alcoholics Anonymous were told that its program and fellowship were “spiritual but not religious” – a formulation that would wildfire through the larger culture in the 1990s.

In the 1980s, meanwhile, some members of Alcoholics Anonymous who felt oppressed by its religiosity and who, more importantly from the perspective of AA itself, saw evidence that the fellowshipʼs religiosity was alienating new members and keeping still others away from even trying its program, departed AA to found two secular counterparts: Secular Organizations for Sobriety and Rational Recovery . Even before that decade, in 1975, a group of Chicago AA members formed “Alcoholics Anonymous for Atheists and Agnostics”, more familiarly known as “Quad-A”. Other similarly motivated diversely named groups formed in various places over the years, but the next significant development took place in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, in 2009 and 2010, when the groups “Beyond Belief” and “We Agnostics”, recognizing the need to make their availability more widely known, formed the website, AA Agnostica. A more complete and detailed history of atheists and agnostics in Alcoholics Anonymous may be found at that website: A History of Agnostic Groups in AA.

4. Leading Up To the Present: Lines Are Drawn

A History of Agnostics in AA. The story told there begins not in 1975 but decades later, in 2011, when the Greater Toronto Area Alcoholics Anonymous Intergroup “passed a motion at its regular monthly meeting that the two groups [“Beyond Belief” and “We Agnostics”] be removed from the meeting books directory, the GTA AA website, and the list of meetings given over the phone by Intergroup to newcomers”. For despite a long history of tolerance within Alcoholics Anonymous, and the reality that the General Service Office of Alcoholics Anonymous recognizes atheist and agnostic groups, the era that began on 11 September 2001 (and was reinforced on 11 March 2004 and 7 July 2005) – labeled by Jürgen Habermas the “post-secular” epoch – brought to a head the long-simmering disagreement within AA between its “Big Book Fundamentalists” and its “Modernizing Secularizers”.

The “Big Book Fundamentalists” draw their inspiration and practice from their understanding of how Alcoholics Anonymous functioned at its birthplace in Akron, Ohio, during the mid-1930s, when the alcoholics met as “the alcoholic squadron” of the Oxford Group, and in the early-1940s Cleveland “Beginners’ Meetings” offspring of that approach. Although this style infuses many groups to varying extents, it finds its most explicit expression in the “Primary Purpose” and “Back to Basics” movements founded within AA in 1988 and 1995, respectively . Followers of these movements continue to give lip-service to the “spiritual rather than religious” shibboleth, but members and groups formed in this Akronite tradition insist on a brand of “spirituality” that harbors no room for disagreement about a very explicitly Christian content. Such explicitness spans efforts to Christianize early AA history, elevate Christian literature on par with AA’s own literature, and assert Christian conversion as a central mechanism of AA’s effectiveness.

The “Secularizers”, meanwhile, interpret the “post-secular” eraʼs reality in a way more congruent with the Habermas understanding. Their “Awareness of What is Missing” focuses on the steadily increasing number of “nones” responding to surveys of religious affiliation. These “nones” tend to be younger, and in surveys that asked their thoughts on the subject, most replied that they were “spiritual but not religious” . Some of these had problems with alcohol and drugs, and some of those who tried Alcoholics Anonymous found it “too religious” for their comfort. The members of atheist/agnostic AA groups generally direct their 12th Step efforts at this population, seeking to “make AA safe for atheists” .

5. Recovery Spirituality

The Little Book of Atheist SpiritualityA true “Recovery Spirituality” will embrace both the quasi-religious spirituality of the “Big Book Fundamentalists” and a more secular spirituality in which atheists and agnostics who have “the only requirement for AA membership…a desire to stop drinking”, can also find a helpful home .

Although “secular spirituality” is not the same as “atheist [or agnostic] spirituality”, it is important to examine the approach of these groups in some detail, for the vast majority of AA members – including most who belong to atheist or agnostic groups – view spirituality as the key to what makes AA work . Some secularizers, especially a few who are less atheist than anti-theist , reject the term spirituality, but several recent books argue for its retention. As early as 2002, University of Texas philosopher Robert C. Solomon published Spirituality for the Skeptic , describing spirituality as thoughtfulness, and suggesting that “spirituality, like philosophy, involves those questions that have no ultimate answers” and must be understood, ultimately, “in terms of the transformation of the self” . Within the next decade and just beyond, other writers developed that insight, at times explicitly exploring an “atheist spirituality.” André Comte-Sponvilleʼs The Little Book of Atheist Spirituality, Ronald Dworkinʼs Religion Without God , and Sam Harris’s Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality Without Religion detailed in varying degrees the content of such an approach.

Meanwhile, specifically in the addictions field, Marya Hornbacherʼs Waiting: A Non-Believerʼs Higher Power , Vince Hawkinsʼs An Atheists [sic] Unofficial Guide to AA , Roger C.ʼs The Little Book: A Collection of Alternative 12 Steps, Archer Voxx’s The Five Keys: 12 Step Recovery Without A God , John Lauritsenʼs A Freethinker in Alcoholics Anonymous , and Adam N.ʼs Common Sense Recovery: An Atheist’s Guide to Alcoholics Anonymous all offered concrete suggestions on how those who resisted the “God-talk” in Alcoholics Anonymous might nevertheless live that program and its spirituality within that fellowship. Also, true to larger AA practice, the year 2013 brought the secularizersʼ own meditation book, Beyond Belief: Agnostic Musings for 12 Step Life: finally, a daily reflection book for nonbelievers, freethinkers and everyone, reflecting the experience of someone who enjoyed 38 years of continuous sobriety .

The varied vocabulary in the above suggests an important point. Even recalling the diverse names by which atheists and agnostics refer to themselves – “unbeliever”, “non-believer”, “freethinker”, “unconventional believer”, “humanist”, and surely there are others – alcoholic atheists and agnostics are not the only ones seeking and practicing a secular spirituality . Spirituality, secular or otherwise, escapes clear definition: there are simply too many definitions. Although we deem the best available discussion of spirituality to be that offered by Sandra Marie Schneiders , for the purposes of this article, we adopt the brief, broad definition set forth by Celia Kourie.

Spirituality refers to the raison-d’être of one’s existence, the meaning and values to which one ascribes. Thus everyone embodies a spirituality. It should be seen in a wider context to refer to the deepest dimension of the human person. It refers therefore to the ‘ultimate values’ that give meaning to our lives.

“Secular spirituality”, as we use the term, embraces that understanding .

Spirituality of any kind, as a non-material entity, is impossible to measure directly . There exists a wealth of indirect measurements, with attention paid to such qualities as “self-acceptance” or “purpose in life”. But as Harold Koenig has effectively criticized, measuring “spirituality” with “indicators of good mental health” – which seems the practice of most such research—is “meaningless and tautological”. The same seems true of equating spirituality with “positive emotions”. But what, then, can be said of “atheist spirituality” or—more precisely for our purposes—“secular spirituality”, and what light does that phenomenon shed on the spirituality found in AA groups and meetings?

6. A Secular Spirituality

Waking UpThe advantage of studying secular spirituality in some detail is that thus reducing the phenomenon of spirituality to a bare minimum allows seeing more clearly its essence. Admittedly, the meetings we attended from which we derive our analysis were populated mainly by Christians and Jews, with a substantial minority of these identifying themselves as “spiritual rather than religious”, with fewer agnostics and atheists, even fewer who professed a Westernized Buddhism, very few Muslims, and none who identified as Hindus. We have tried to supplement that insofar as possible with our reading.

In barest summary, pondering what we heard across the meetings we have attended over the years as well as the stories that we have read in different sources, the spirituality that we witnessed can be summed up in two words – the prepositions beyond and between. These form the schema of any secular spirituality, the skeleton of AA spirituality. There is more to that spirituality, of course: that skeleton is enfleshed and clothed, and below, we will examine six such qualities similarly derived from our listening and reading. But we must begin with those prepositions, two words that, we think, aptly and adequately summarize 12-Step spirituality, whether religious or secular, whether of the relative newcomer or the veteran old-timer.

“Beyond”: Beyond derives from the Old English begeondan, a root not found in other Germanic languages, a preposition meaning literally “on the farther side”. It thus implies some kind of barrier, but a barrier that does not obstruct seeing – and perhaps even going – beyond, farther. The barrier, then, is in some way permeable: it invites – indeed teases – transgression. Beyond pulls forwards; it is not content with stasis. Beyond hints “more”, but of different, not of the same. That which is beyond, then, in some way beyonds us, in the striking verb pioneered by literary scholar Kenneth Burke .

Beyond awakens and pulls to transcendence. For many ages – for most humans for most of human history – beyond pulled towards the horizon. It implied horizontal movement, an invitation to explore. But just about always for some, and in the age of flight and space travel for just about all, beyond points also vertically, pulling upwards, to new heights. Even before flight, of course, many religious traditions located “heaven” in the heavens. Beyond, then, suggests a dual transcendence: out from the narrow confines of the self-centered self; and up toward some reality greater than, larger than, the self-involved self. “Selfishness—self-centeredness! That, we think, is the root of our troubles”, AA’s basic text suggests , capturing a truism that applies not only to alcoholics.

“Beyond’s” vertical transcendence implies a going out and up, a movement toward some reality. This need not entail “higher” in the sense of some kind of heaven or sky-god; it rather connotes a getting-out-of-self to that which is “higher” or greater in the sense of some ideal or of some reality larger than the bare, narrow self. That reality might be one of the classic transcendentals” – beauty, goodness, truth – or one of the “AA transcendentals” such as gratitude or sobriety itself. It might also point to the power of the AA group or of the fellowship or program itself; there is no need for that “power” to be capitalized, though some may choose to do so. But in whatever way, any spirituality – including any secular spirituality – beyonds its adherents, pulling them to a transcendence to reality larger/greater than the bare self.

This beyonding, this transcending escape from the bondage of self, opens to a capacity for the wonder and awe that grounds all spirituality. Whether in the wondrous perfection of a newborn infant or the sublime grandeur of a glimpsed universe, the recognition and acceptance that there is reality that transcends self opens to a genuinely new perception and appreciation of all reality. This recognition is not easily granted: the bogey of self does not readily surrender its centrality. But when it does, the resulting new vision is greater even than the “new pair of glasses” promised by one of AA’s earliest members .

And as a post-secular literature makes clear, transcendence can be horizontal as well as vertical [67,121–124]. Spirituality’s second preposition, between, offers a specification of “beyond’s” horizontal transcendence: it connects with others. “Between” is more apt than “beside” because it connotes actual connection rather than mere next-ness: there is a “something” between, something linking, as the Oxford English Dictionary puts it: “in reference to any objective relation uniting two parties, and holding them in a certain connection (italics added)”. Spirituality, then, in “pulling beyond” also pulls to, connects. And what is there, horizontally beyond? At first, most obvious level, beyond the “self” are others, and between captures the nature of that relationship, the between-ness of equal connection, a connection of equals. “Between” thus orients to the fundamental first reality that the author of the Book of Genesis put in the mouth of the Creator God: “It is not good for man to be alone.” Nor is this an exclusively “religious” observation: given the development of sexual reproduction, some being in the mist of evolutionary pre-history made – and implemented – the same observation, reaching out in some way to an-other [125]. Fundamental to all living existence is the need for others, in one form or another.

This spiritually based human need-for-others, however, has some unique qualities, and one of the most important is the reality of its mutuality. Mutual relationships involve not the giving or getting of competition, nor even the “giving and getting” of cooperation, but a very real and genuine giving by getting, getting by giving [126,127]. This, then, is a very special and even unique kind of between-ness. Mutual bonds are more than alternately reciprocal. And to appreciate the centrality of this to the 12-Step program, we need to recall the basic first two happenings in the story of Alcoholics Anonymous, the first 12-Step program.

AA co-founder Bill Wilson, whose “spiritual experience” in New York Cityʼs Towns Hospital in December 1934 had propelled into sobriety, was in Akron, Ohio, in May of 1935. The proxy-fight he was there to pursue was failing, and Bill dejectedly paced the lonely hotel lobby, catching the sounds of pleasant chatter and the tinkle of ice cubes in the adjacent bar, when an old familiar thought rose: “I need a drink”. Recalling how trying to help other alcoholics had freed him of that craving over the preceding months, even though none he had approached had stayed dry, Wilson walked to the lobby telephone booth and began the series of calls that led him the next day to a meeting with Dr. Robert Holbrook Smith, a local surgeon with a known “drink problem”.

Before his journey to Akron, Wilsonʼs physician, Dr. William Duncan Silkworth, had urged him to “stop preaching at the drunks – give them the medical stuff, the hopelessness, etc.”. But how could Wilson teach medicine to a physician? So the next day when they met, Bill simply told Dr. Bob his story, and the surgeon identified and expressed willingness to try what Wilson had done. Bill described this meeting twenty years later, at AA’s “Coming of Age” convention:

You see, our talk was a completely mutual thing. I knew that I needed this alcoholic as much as he needed me. This was it. And this mutual give-and-take is at the very heart of all of AAʼs Twelfth Step work today ([17], p.70, italics in the original).

Bob went on one last “toot” at a medical convention a month later, and it was only after his final alcoholic drink on 17 June 1935, that AAʼs core spiritual insight was nailed down. Not long after, Bill and Bob visited the hospitalized drunk who would become “AA #3”, Bill D. They told Bill D. their stories and then asked him to let them know as soon as possible whether or not he was interested in what they had to offer, for if he was not, they had to seek out others, because it was only by carrying their message to other alcoholics that they themselves could remain sober. Bill D. later recorded his thought on hearing that:

All the other people that had talked to me wanted to help me, and my pride prevented me from listening to them, and caused only resentment on my part, but I felt as if I would be a real stinker if I did not listen to a couple of fellows for a short time, if that would cure them ([9], p. 185, italics in the original).

The Twelfth Step of Alcoholics Anonymous is often misunderstood by those outside the fellowship: “Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these Steps, we tried to carry this message to alcoholics…”

“But,” somebody asks, “what if that drunk you seek out doesn’t want to stop drinking? What do you do about a ‘failed’ 12th Step call?”

“Well, a ‘failed 12th Step call’ is one on which you drink. Itʼs your 12th Step call, you are ‘carrying the message’, and so if you stay sober, the call is a success.”

We may reach up; we must reach out. The topic here is spirituality, remember – that essentially ineffable reality that is at the core of our human be-ing. The wisdom of the human race – our art, music, literature – all attest to our bonds with each other. Indeed, they bond – bind – us with each other. To look beyond is to look and to seek outside of self – up and around. To look between is to look “around” and to discover that we are bonded to/with each other. Transcendence must be horizontal as well as vertical: to look only “up”, to reach only “up”, is to feel one’s aloneness, and standing alone can be dizzying. To realize our full humanity we must also reach out, and when we do look around, between, we discover our connections – the between-nesses that link us with others .

Genuine spirituality reminds us of our between-nesses as well as our beyond-ing.

No, it does more than “remind” us: spirituality consists in that reach, those links. We are beyonding and betweening beings. That is why we are here. One is tempted to say that “Alone, we are nothing.”But only tempted, and even that only at very unusual moments. For in the most real sense, it is impossible to be “alone”—a lone. Connection is always present. The question is, do we recognize it, live it, honor it? We may say, with John Donne, that “No one is an island”; but how well are we living our prepositions?

AAʼs 12-Step spirituality does not end here. Beyond and between are the foundation, the skeleton: the actual living and experiencing of spirituality comprises certain phenomena, experiences. In our years of listening to and reading 12-Step stories, six different experiences have emerged with some consistency. This does not mean that all of them are heard in every story. It does mean that just about every story delineates and describes at least one, and usually two or three of these experiences. To name them: Release, Gratitude, Humility, Tolerance, Forgiveness, and Being-at-home.

7. The Contents of Recovery Spirituality

Release: especially in early recovery, but also at later critical junctures of the recovering life, the individual experiences a profound sense of being freed: for one who has been addicted, there is no better term to describe the removal of that obsession-compulsion. This is sometimes described as the feeling that a great weight has been lifted, or as if chains in which one has been bound have fallen away. In each case, the sense is not of freeing oneself but of discovering that one has been unbound, liberated, set free. This sense of “being released”, interestingly, seems to come only to those who have released, who have let go—most obviously in this setting of alcohol or some other drug of choice: it seems, then, that one becomes able to experience release only after one has oneself performed an act of releasing, of letting go.

Gratitude: the experience of thankfulness, the recognition that one has been gift-ed, has received gifts . Sometimes expressed as a corollary of Release, the recovering person describes an appreciation for what is recognized as a freely bestowed gift. Within Alcoholics Anonymous, this is often posited as gratitude for “the gift of sobriety”, for most recovered alcoholics remember how they had been unable to attain recovery on their own, despite their most genuine and valiant efforts. But beyond this, immersion in and internalization of the 12-Step program begets a special kind of vision that enables recognizing new realities, realities previously ignored or taken for granted or simply not seen, realities that one now can recognize. Gratitude anchors sobriety. Members who express difficulty with living some aspect of the 12-Step program are often encouraged to “write out a ‘gratitude list’ – the things you have to be grateful for”. Trite and even cruel as such an admonition may sound to some outsider, experience attests that those who have been through it know that “it works” .

Humility: the recognition and acceptance that one is neither all nor nothing. In an era that worships celebrity, humility does not enjoy a good press. Some might wish to be thought humble, but no one wants the real thing or what is commonly mistaken to be the real thing, a sycophantic creepiness. But real humility is simply the acceptance that one is of some value, but not of infinite value: one is “not God”. To be human is to be middling. More vividly, in the memorable phrasing of anthropologist Ernest Becker: “Man is a god who shits” ([139], p. 58). On the one hand, we are capable of love and altruism and generosity and many wonderful things, but it is also true that periodically, we have to squat down and be reminded that we are also made of decay and will one day return to stinking decay. Humility is simply what keeps both of those realities in appropriately close awareness .

Tolerance, of course, flows from “all of the above”. It is difficult to be self-righteously judgmental when one is aware of one’s middling status as a receiver of the gift of a fundamental freeing. Having “hit bottom”, one learns to look up and around rather than down. Recognizing, really experiencing the realities laid bare by humility, aware of the gifts one has received, it does not necessarily become easier to put up with the inanities of others, but if we see those in the context of what we are learning about ourselves we may become able to smile a bit at our own upset. There are many wisdom stories in which the self-righteous person asks the god for what she/he “deserves”; and then is crushed by the discovery of what that will in fact entail. The recovering alcoholic knows better. Aware of that wisdom, one hesitates to judge. In fact, one is likely to be terrified at the very possibility.

Forgiveness: “Resentment is the number one offender”, the AA “Big Book” cautions, going on to declare that “It destroys more alcoholics than anything else. From it stem all forms of spiritual disease.”

Dostoyevsky and Nietzsche were the great explorers of ressentiment, but active alcoholics may be its pre-eminent practitioners

. The opposite of resentment is forgiveness, and research on forgiveness verifies its spiritual nature in that it is one of those realities that cannot be “willed”. Forgiveness in fact becomes more impossible the harder one tries to will it. As is true of all spiritual realities, forgiveness becomes possible only when will is replaced by willingness: it results not from effort but from openness. Research also suggests how that openness comes about: what makes forgiveness possible is the experience of being forgiven. How one attains that is one role of AAʼs Ninth Step, making direct amends to those one has injured. Apologies are not amends. Some effort to re-even the scales of justice is required, and sometimes – certainly not always – the individual who has been wronged expresses forgiveness. Experiencing this is to discover that being forgiven is a genuinely spiritual experience, one that one wants to pass on to others .

Being-at-Home: Everyone needs a sense of “community” – the deep experience of being in some way at one with some others. Unlike other communities that one may join, “home” is a place where we belong because it is where our very weaknesses and flaws fit in and are in fact the way we “fit in”. Once upon a time, in infancy and early childhood, many if not most people experienced that. It was called “family”. Our need for it does not cease as we age. And so we seek such places. Also once upon a time, this was the function of churches, which began as the place where those conscious of being sinners gathered together. Interestingly, this is to some extent replicated for some new to Alcoholics Anonymous, who park their cars blocks away from the meeting-place lest someone see them attending. But even after one becomes willing to park close-in, the key thing about such places is that one fits into them not because of strong points, competencies, but through mutually acknowledged flaws, weaknesses, inabilities…something one can’t do: “drink alcohol like ‘normal’ people”. To find and dwell in such a place, the whole history of spirituality attests, is an essential facet of spirituality.

Secular Spirituality and the Future of AA

In the United States, the percentage of religious “nones” – the non-affiliated – had risen to close to 20% in 2012, and 46% of the overall population “seldom or never attend religious services” . Across the pond, the 2009 British Attitudes Survey for the first time recorded more “No Religion” (50.9%) than “Christian” (43.1%) respondents; and according to a 2011 YouGov poll, only 34% of UK citizens claimed they believed in a God or gods. A February 2012 YouGov survey found 43% of respondents claiming to belong to a religion and 76% claiming they were not very religious or not religious at all . Matters seem not much different in the rest of Europe.

Still, it seems, few “nones” in any nation label themselves atheist or agnostic. Most are younger, and listening to them and to their music, the term “secular spirituality” may be a good fit: surely their beyonding and betweening are evident and real, although so is a focus on “self”. What might those changes and this reality portend for the Alcoholics Anonymous that presents itself as “a spiritual program”? In our view, the two opposite responses noted earlier within AA will probably continue to be operative into the foreseeable future. Remember, however, that these are “opposites” and so deal with extremes. The great majority of AA members will more than likely continue to settle somewhere comfortably in-between, generally tolerating the extremes but probably more often than not seeking out groups that better fit their middling inclinations.

Still, especially if – or as – the animus of “post-secularity” spreads and is internalized by a population increasingly aware of Islamic reality, the “Big Book Fundamentalists” may grow stronger and more numerous. It is unclear whether they will abandon their misconstrual of a 1990 General Service Office report on membership, claiming that it portrays AA’s “success rate” as 5% or less, which they allege demonstrates the necessity of their own more stringent approach. Carefully rigorous studies refute that 5% claim , but those with this mindset do not demonstrate much openness to the findings of research.

Although the variety among AA groups has long embraced a spectrum from more “conservative” to more “liberal” approaches to living the Twelve Steps, the end of the twentieth century found Alcoholics Anonymous unsurprisingly enmeshed in the post-modern rebirth of fundamentalisms . Standing at one far end of that spectrum, both the “Primary Purpose” (1988) and “Back to Basics” (1995) movements seek to bring about within AA a return to a largely imagined pristine purity. Two observations may be made about these programs: (1) they have helped some, especially among the more religiously inclined, who had been unable to “get the program” in more ordinary AA; and (2) they have estranged at least an equal number who are alienated by their heavy emphasis on a very explicit “old time religion”. Although this site is less than fully accepting of these groups, a useful and generally balanced perspective on both groups, and on AA “Big Book Fundamentalists” in general, is available .

On the opposite side stand the “Modernizing Secularizers” in Alcoholics Anonymous, some of whom not only reject the heavy religious emphasis of the “Back to Basics” enthusiasts but also are antagonized by even the bare mentions of “God” in the Twelve Steps. Although far from all

“Modernizing Secularizers” identify as atheists or agnostics, such are the most avid objectors to the sometimes-practice of closing AA meetings with the Lord’s Prayer and favor finding substitutes for the “God” noun and pronouns in the Steps themselves. And although atheist and agnostic AA groups are recognized by the Fellowshipʼs General Service Office, some religiously inclined AA members refuse to acknowledge them.

The developing significance of the “Modernizing Secularizers” was underlined in November 2014, when WAAFT – We Agnostics, Atheists, and Free Thinkers – held its first national gathering in Santa Monica, California. The convention was attended by some 300, including visitors from Australia, Turkey, France, and Spain, and was addressed by the current manager of the Alcoholics Anonymous General Service Office and by a former non-alcoholic (and Episcopal minister) Head Trustee of the fellowship, both of whom warmly praised the group for what they offer the AA fellowship as a whole. The “Modernizing Secularizer” perspective is best set forth in the books referenced earlier [83–89] and at the AA Agnostica website , the archives of which contain descriptions of the WAAFT convention.

The secular approach and the growing reality of atheist and agnostic meetings of Alcoholics Anonymous may become of increasing importance especially in the United States of America. In at least two of that nation’s nine judicial districts, AA has been deemed sufficiently “religious” that prisoners and parolees cannot be required to attend its meetings as a condition of their rehabilitation. In its 1996 Griffin v. Coughlin decision, the 2nd Circuit’s appellate court ruled that “Adherence to the AA fellowship entails engagement in religious activity and religious proselytization” . Just over a decade later, the Ninth United States Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the constitutional dividing line between church and state is so clear that a parole officer can be sued for damages for ordering a parolee to go through rehabilitation at Alcoholics Anonymous or an affiliated program for drug addicts . Two useful summaries, each with links to specific legal sources, may be found at.

Faithful to the AA Tradition of avoiding public controversy and having no opinion on outside issues, the New York General Service Office of Alcoholics Anonymous declines to comment on those decisions or on the sometimes distorted reporting of them that has appeared in the public press or in private commentaries. Some members and students of AA have however suggested that the existence and current increase of atheist and agnostic AA groups rebut such claims, demonstrating their falsity. It will probably require another appellate court decision to test that claim. Until such time, it is not true that “American courts have found that Alcoholics Anonymous is a religion”; but it is accurate to observe that those who supervise United States penology practices need to keep in mind the nation’s constitutional separation of church and state.

8. Conclusions

Not GodWithin the “Recovery Spirituality” that no one doubts can embrace a religiously oriented spirituality, there also exists room for a “secular spirituality” that can include even “an atheist spirituality”. Its core content is summarized in the two prepositions, beyond and between. How those prepositions are specified varies among AA groups, the main difference in the United States being geographic. In the American South, lower mid-West, and southwest, many meeting participants tend to offer an explicitly Christian witness, often mentioning “Jesus Christ” as well as some relationship with “God”. On the coasts, in the northeast, and upper mid-West, such effusions are rare, and it is more common for the Serenity Prayer instead of the Lord’s Prayer to close meetings that sometimes began with a reading from the also Conference-approved Living Sober rather than the God-heavy “How It Works”. Some may mention their “Higher Power” or “God”, but rarely as central to their stories.

But even within those parameters, in the vast majority of AA groups, the topic of “spirituality” is rarely raised. Most speakers talk about, and most discussions revolve around, more quotidian areas where members are endeavoring to live the 12-Step program: a lack of patience with oneʼs spouse, inappropriate concern over one’s childrenʼs activities, anxiety over a coming medical diagnosis, worry about an employment situation, and the list goes on. When a newcomer is present, members usually tell how they first came to AA What comes out in those talks and “shares” usually are hints and reminders of the six “spirituality facets” noted above: Release, Gratitude, Humility, Tolerance, Forgiveness, and a sense of Being-at-home. There are no labels, denominational or otherwise, for this spirituality. It simply is. And on the basis of available evidence, it will continue to be.